Diary: Painting rosebushes

[Content warning: regret, threat of decapitation]

Dear Diary,

I’ve been in the attic.

When I was six years old and in the second year of primary school, our teacher introduced the class to ‘Alice's Adventures in Wonderland’, by Lewis Carroll.

I can’t remember whether the book was read to us or whether we were given a shorter summary of the story, but there are two feelings I still remember clearly from the experience.

The first is a strong sense of unease and confusion. There was a talking white rabbit, the girl fell down a hole, then found herself in a very strange and disconcerting underground world. The creatures and the characters she met seemed chaotic and sinister. None of it made sense to me, and the imagery formed in my head was dark and distressing. I could feel a knot tightening in my stomach.

To this day I still get a sense of this whenever I see a reference to the book or a trailer for a movie. I should probably exorcise these demons by reading the book as an adult, but I just can’t face it.

The second feeling occurred a little later, and it’s about my father.

At some point after the storytelling had ended, and to engage our imaginations, our teacher instructed us to paint a scene from the story. This was a messy business. A large class of six-year-olds spreading large sheets of paper over desks, grabbing paint-palette mixing trays with large round paint blocks, spilling water pots, and competing for the best wooden-handled, course-haired paintbrushes.

I painted the scene where three gardeners were painting the rosebushes. They had planted white roses by mistake and were frantically painting the flowers red to avoid the wrath of the Queen, who happened to be frighteningly intolerant and had only one solution for every annoyance, “Off with their heads”! I was afraid for the gardeners, and equally terrified of the Queen.

Thanks to my father, the painting survives to this day.

At the end of term, all the parents flooded into our classroom. We had each prepared some evidence of our classwork, including our paintings, and displayed them on our desks.

With hindsight, it was unusual to see both my mother and father attend a parents' event while I was present. I would later become accustomed to waiting at home in the evening, filled with anxiety and dreading their disappointment, or worse.

My parents surveyed my offerings. My father, on seeing my painting, seemed slightly startled, “Did you do this”? It was an unexpected reaction and, for an instant, I wasn’t sure if I was in some kind of trouble. Now on high alert, I replied, “yes”, and winced inside.

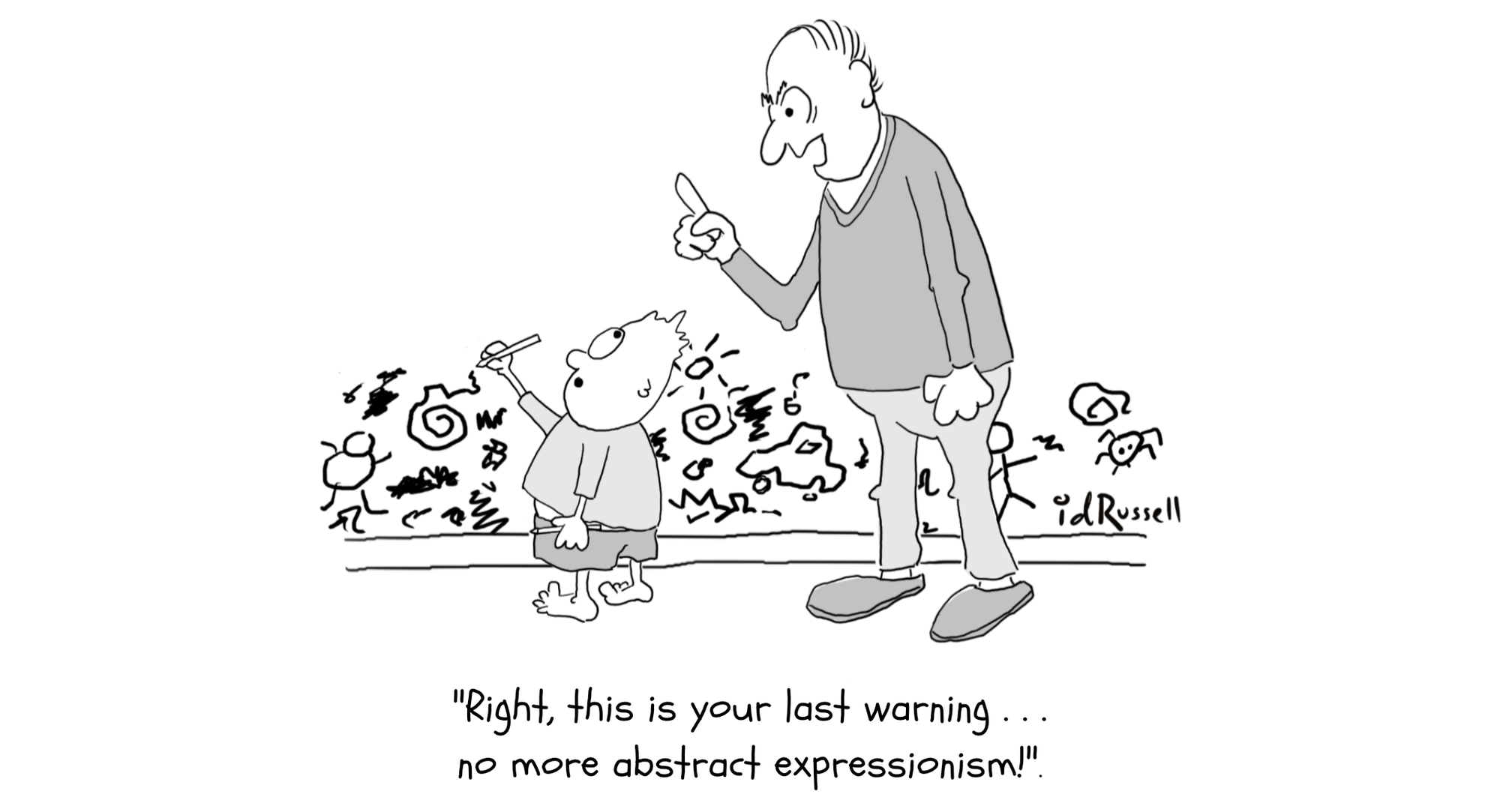

My father was not easily impressed nor generous with his encouragement or support for activities outside his own interests. I grew to understand him as inflexible and difficult to please. He became increasingly intolerant over the years and quick to react. Like the Queen in the story, someone whose volatility could compel you to paint rosebushes.

These days I occasionally see him in the mirror, or through my own actions, and sometimes there are moments of recognition - or a new understanding - of our similarities, our neurological inheritance.

“This is brilliant”, he said, or words to that effect. His surprise blossomed and he questioned me about the subject of the painting and my use of colours and ‘abstract’, whatever that was. He was genuinely impressed. Proud.

It took me a long time to process that moment. My father could be relied upon to accentuate the negative, his way of encouragement, but never to praise so openly.

A short time later the painting reappeared at our home. My father, ever resourceful and extremely talented in his own ways, had made and mounted it in a simple wooden picture frame.

As a young child, I was surprised and somewhat bewildered by his attraction to the painting, and aware that it seemed to mean a lot more to him than it did to me, especially given my aversion to the story, but this gesture, this affirmation, meant the world to me.

It wasn’t just the painting I found in my parents’ attic over half a century later. There was also something unsaid. A new regret.

Diary

Member discussion